Divya Jain is pursuing her master’s degree in Urban Design at the Delhi School of Planning and Architecture (Delhi SPA).

Fig. 1: Vision Through the lens of shapes formed by bricks. Photo: Divya Jain

Fig. 2: Brick covered in the spiritual layer. Photo: Divya Jain.

FIg. 3: Brick with the layer of a frame. Photo: Divya Jain.

“Thank you, kind sir,” said the child, a faint trace of British accent clearly heard. “Mummy, please take a picture,” he says, while facing towards the camera and posing and raising his hand for the handshake. The elderly man, surprised by his gesture, had tears in his eyes. Overwhelmed by the sudden respect, he returned the firm handshake and then brought forward his other hand on top of the boy’s head. A sign of blessing. This silent dialogue marked the space with its essence. Then I focused on myself. On how I could taste the sweetness of culture at the Patan Durbar Square, without even touching it. On how I could sample the freedom rushing through my veins, knowing that I am surrounded by the wilderness of that brown texture of Bricks.

Standing at the square, looking ahead, I could taste the energy felt by everyone that passed by. It often happens that certain colors and visions evoke our oral sensations. But certain spaces too? That too man-made? Do we really have that power to build something that gets our heart pumping in anticipation, that gets our mind racing to the point that we feel free and exhilarated? The most intimate experience of architecture is experienced with the subconscious feel of taste. You never know what you’ll discover.

While contemplating my walks over the past six days, the one thing that struck me was the element of brick used in the urban space. The similar color of the bricks is integrated with the environment, giving a scope for the continuous preservation of the architecture while maintaining a harmony and visual continuity with its surroundings. The traditional brick architecture has evolved over hundreds of years into a uniform construction, reflecting and integrating the demands of culture, religion, and daily activities, as well as environmental considerations. Within the coherence of style and materials, building height, and elevation symmetry, there is a rich diversity of detail and decoration.

Fig. 4: Brick ornamentation giving an identity (left). Fig. 5: Brick merging with other elements (right). Photos by Divya Jain.

The Kathmandu region has a very good type of clay which, when fired at a high temperature, produces fine quality red brick and tile, and the traditional brick molds produce bricks similar in form and size to modern bricks. Other types of mold have also been used for cornices and moldings. The best type of brick, used for front elevations, is known as chikā ape, and is smoothed and polished with oil before firing, giving it a shiny surface. The mortar of old houses is mainly clay, as in the past lime was not widely available in the valley. The walls can be as thick as 70 centimeters. In most houses, fired brick is used only for the surface of the walls, while the core of the walls is constructed of unbaked brick.

Traditional, Common, and Modern Brick Construction Techniques

When looking at construction techniques that are commonly used in Kathmandu Valley, we can roughly divide them into three eras, which I have chosen to call traditional, common, and modern.

Traditional: The vernacular Newar architecture consists of a three-layered brick wall with a wooden bear structure and wooden detailing. Traditionally, this style used wedges and perforations in the brick wall to join the wooden construction. The bears are joined in the comers to create a box, which allowed the constructed building to move as one entity.

Common: This construction consists of two layers of traditional fired bricks that are joined together with concrete ribbons and strengthened with concrete steel. The walls are usually not cladded, which creates a distinguished architectural expression that showcases the building's construction. This has been a common feature in the history of Nepalese architecture, where the wooden construction has been visible in the facade.

Modern: The construction methods used in Nepal today often consist of a brick wall that is framed with another material, such as wood, concrete, or steel. Many of the modern building techniques used in Kathmandu Valley use an interlocking brick that has better seismic capacity than the traditional fired brick. The brick wall is reinforced with horizontal and vertical rebars and filled with a concrete mix to stabilize the wall. This makes the brick wall stronger and less dependent on a primary structure. Some of the interlocking bricks allow for the concrete ribbons to be hidden within the wall, which creates a new architectural expression where the construction is less visible in the facade. The bricks can be used as the load bearing structure in smaller buildings but are often used together with either a steel or concrete structure.

During a walk through the streets of Patan, headed by Rohit Ranjitkar, I realized that, post-earthquake, when an old house is reconstructed, it is not replaced by a soulless concrete and glass box. Rather, it is usually either constructed as a modern building with new brick façade, or with a traditional brick facade that is in harmony with its surroundings. This to me signifies the richness of the time periods referenced, as well the significant value that people still hold for the use of brick construction.

Away from the square, debris had silted onto the lane between two rows of tottering residences. Two young men were laughing among themselves, “I think we had better become architects now,” one said. “Forget about your science degree.” This made me question myself about the impression of the bricks because, when the display of nuances (like vendors inviting customers to shop, or the residents gossiping sitting outside) dies away, the building becomes an array of patient silence. It compels us to be aware of our own fundamental solitude. It not only carries the sounds of the present but also the echoes of past, which have become distant memories, only to be awakened by the silence of the very same space.

Therefore, isn’t it okay to consider this brick architecture as heritage, as a step towards the preservation of the culture and the reuse of the built environment?

Brick by brick, generation by generation. Photo: Divya Jain

References:

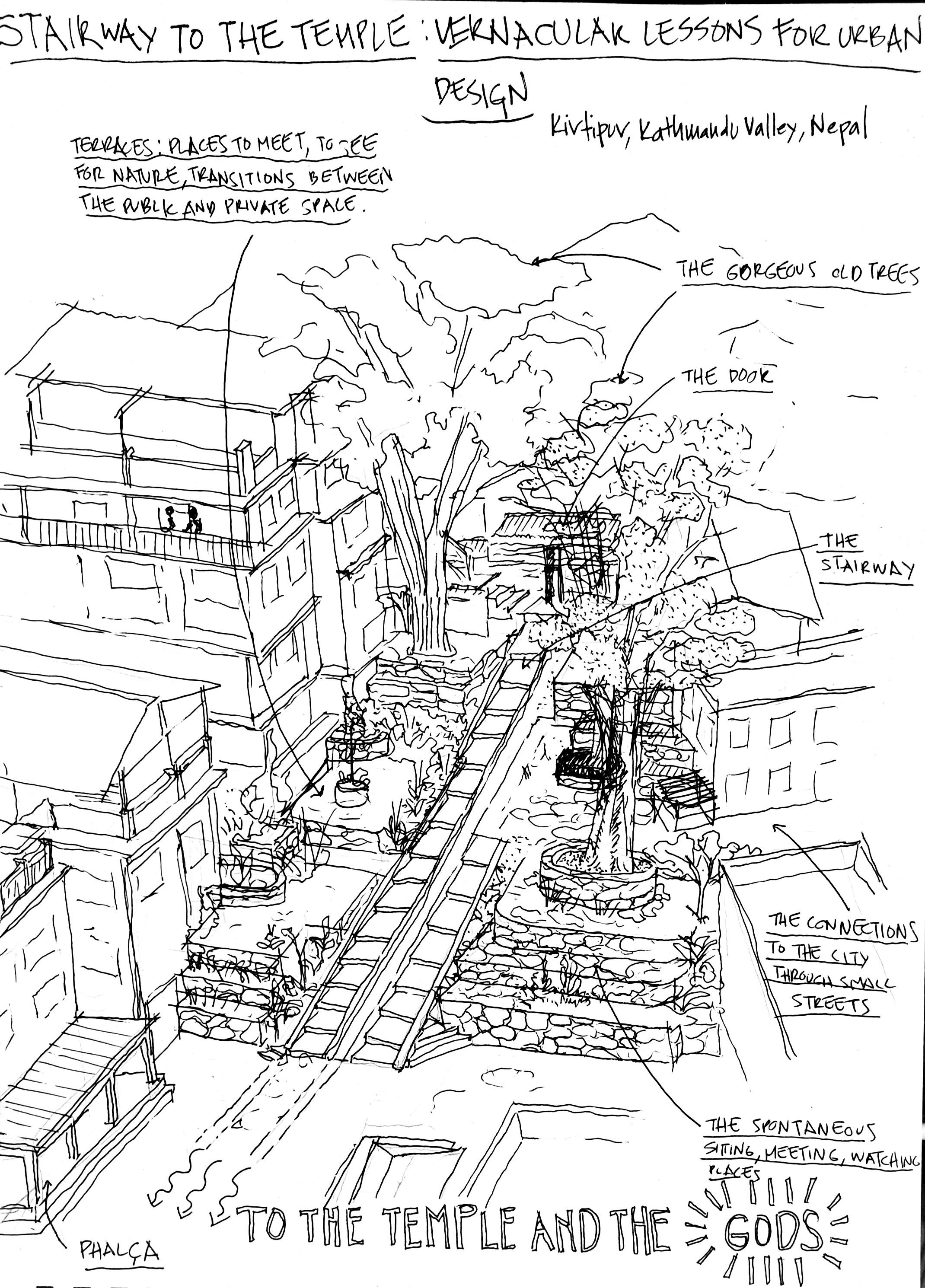

Kirtipur: An Urban Community in Nepal: Its People, Town Planning, Architecture and Arts (First Edition). (n.d.). Araxus