Durlav Rayamajhi is an anthropologist studying Nepali culture, heritage, and myths.

Most of the cultural experts at the summer school pointed out that the Newar community follows both Buddhist and Hindu principles. In all my visits, I always wondered what could symbolize this unique aspect of Newar culture. The answer I got was mandala.

What is a mandala? In his encyclopedic entry on the mandala, author J. J. Mark (2020) writes, “a mandala is an artistic representation of higher thought and deeper meaning designed to focus one's attention on spiritual, emotional, or psychological transformation. Originating from the Hindu scripture Rig Veda (1500-500 BCE), mandala is a very popular art form that many religions around the world, i.e., Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Shintoism, used as symbolic representations to give expressions to different intangible meanings and ideas of a higher being or cosmos. In Sanskrit, ‘mandala’ means circle, representing the cycle of life. In Buddhism, mandala is formed by two words, manda meaning principle and la meaning water that flows between that principle, creating a boundary.”

Intangible elements of culture usually find expression in tangible forms. In the case of Newar culture, the intangible beliefs and ideas about the cosmos, spirituality, and life have found their expression in the form of mandalas with different shapes, geometric designs, and symbolism.

A Kumar Mandala. This and all photos to follow were taken by Durlav Rayamajhi in the Kathmandu Valley.

A mandala set into a tiled floor.

A Kumar Mandala.

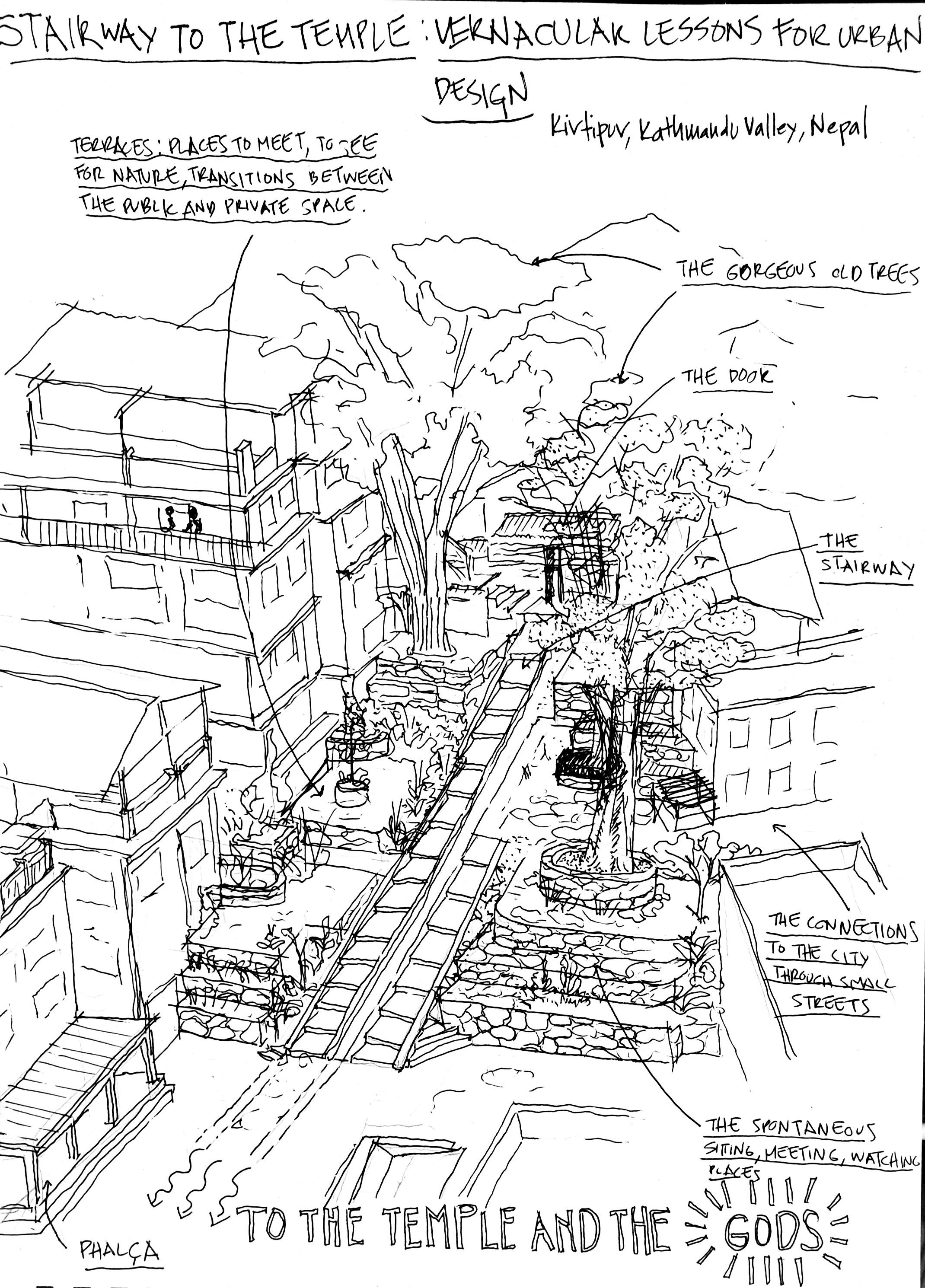

The use of mandalas varies as well. A mandala can be a simple decoration on the wall, a painting, the marker of entry to a Newar house (also known as a Pekhalchi/Pekhlati/Pikhlakhu). The many stupas such as Swayambhunath and Boudhanath, temples such as Kasthamandap, Bagh Bhairab, and many others throughout the valley use mandalas to design these structures. During the Malla period, the whole of the Kathmandu valley was known as the Nepal Mandala, denoting the significance of this form. Rajjan Chitrakar, quoting Tiwari (1989), writes, “some type of plan must have been required for a layout of larger towns of the Malla period and [this] suggests that the concept was derived from a Vaastu Purusha Mandala” (2020). Niels Gutschow writes, “a study of Bhaktapur city suggests that the town has been laid in the form of a Mandala, reflecting the cosmic order transformed into the reality of an urban space” (1993). Meanwhile, J. Gray (2009) writes, “I describe how domestic space, configured in everyday activities as a mandala, is the medium through which abstract cosmological ideas are given tangible form.”

Kumar Mandala

Bajra Mandala

Swayambhunath Stupa Structural Plan

The mandala became a ‘gem’ for me because it embodies many tangible and intangible ideas of Newar culture or the culture of Kathmandu valley. In its smallest form, it represents the entrance to a building, whether it is a temple, house, or stupa, and in its largest form, it represents the entire universe that again cycles back to the day-to-day activities and beliefs of people, completing the cycle.

References:

Chitrakar, R. (2020). “Morphology of traditional towns and the organisation of neighbourhood public spaces in the Kathmandu Valley.” In Revisiting Kathmandu Valley’s Public Realm: Some Insights into Understanding and Managing Its Public Spaces. Nova Science Publishers (pp.1-28).

Gray, J. (2009). “Where truth happens: The Nepali house as Mandala.” Anthropologica, 195-208.

Gutschow, N. (1993). “Bhaktapur: Sacred patterns of a living urban tradition.” Studies in the History of Art, 31, 163-183.

Mark, J. J. (2020, October 6). “Mandala.” World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 15, 2022