Julia Meckl is an MA student at University of Heidelberg in the program ‘Development, Environment, Societies, and History in South Asia’ (MA South Asian Studies) and is a research assistant within Heritage as Placemaking. Her current research focuses on the multiple social lives and contested place of the nagarā kettledrums in the Limbu society of Eastern Nepal.

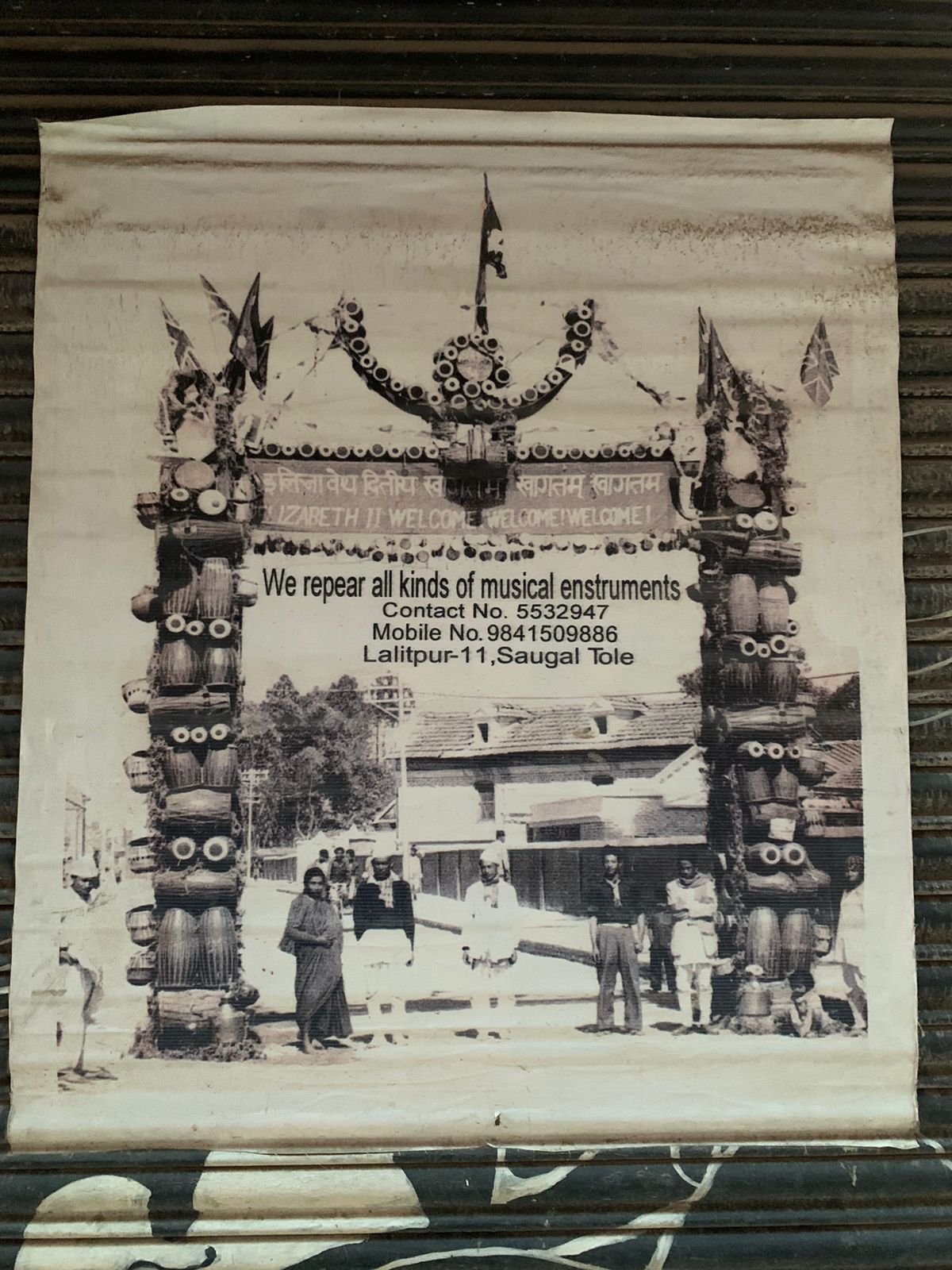

The shop’s advertisement in the alley shows an old photograph of a gate made of drums, created for the visit of the British Queen Elizabeth II to Nepal in 1961. Photo by Julia Meckl.

Nestled in an alley departing from Saugal Tol in Patan lies a true gem. Advertising with the promise “We repair all kinds of instruments,” the Nepali Sanskritik Baja Udyog (Nepali Cultural Instrument Factory) of Hari Lal Kulu and his son Ashish Kulu is both workshop and a cabinet of musical wonders. Stuffed to the ceiling with instruments of all kinds and sizes, old and new – from the pañcai bājā and Newar dhime bājā ensembles, to Tamang ṭuṅgna (a type of lute) and drums from all corners of Nepal and beyond, to classical sitar, European harps and violins, ukuleles and electric guitars. Instruments are built, mended, and may be borrowed. The workshop and its collection manifest the skill trained and transmitted across seven generations of the Kulu family running the shop. Knowledge has been passed down hands-on, from father to son. Today, the shop is both well known to a local audience of musicians and musical groups, as well as to international customers. It is a place where aficionados meet and connect, and where various craftspeople collaborate in the making of an instrument.

According to Ashish Kulu, their family migrated from India many generations back to provide the Malla palace with their musical services. In the past, the whole alley was lined with one workshop after another of Kulu instrument makers.

While drums play a central role in Newar religious and social life, in daily rituals as well as in the festivals, as anthropologist Richard Widdess (2013, 108-9) writes, the drum makers themselves have suffered social stigmatization through their handling of animal skins, thus accrediting them with “water-unacceptable” caste status. The lack of recognition for the profession has made it unattractive for younger generations to continue the craft in the recent past. However, the example of this at once cosmopolitan and deeply rooted workshop in Saugal shows that instrument makers themselves are effecting changes in their social recognition and are being recognized as preservers of Nepal's musical heritage (Ghimire 2017).

The shop nowadays assembles a musical pluriverse, with each instrument having its own transcultural and migratory history. Likewise, each instrument tells stories of who has played and who will play it, for what kinds of purposes and occasions, and who listens. Above the shop, instrument lessons are taught, and musicians can use the space for spontaneous jams or band practice. Thus, the shop becomes a living and truly vibrant archive of urban musical life, defying the separation of “modern” vs “traditional,” and national or ethnic compartmentalization.

A special curiosity that caught my attention at Nepali Sanskritik Baja Udyog are the miniatures of Nepali instruments. While they seem to be only for decoration as they are not functional instruments, they embody the shop’s dedication to musical heritage conservation. These miniatures convey an attachment to specific instruments and their sounds. They connect us to tunes that we know, that are part of our aesthetic experience, that we might personally identify with ourselves, or with other people and places. In this way, the miniatures contribute to make the workshop a space of archiving and exhibiting musical heritage, of playful and skillful innovation of tradition.

The drum makers’ workshop, with mādal, khiñ, dhime, damāhā and nagārā drums. Photo by Julia Meckl.

The miniature instrument workshop. Photo by Julia Meckl.

References:

Ghimire, Sandhya. 2017. “Saving the Sounds: How Is a Family Business Preserving Ancient Nepali Music?” Online Khabar, Oct. 25. Accessed Sept. 2022. https://english.onlinekhabar.com/saving-the-sounds-how-is-a-family-business-preserving-ancient-nepali-music.html

Widdess, Richard. 2013. Dāphā: Sacred Singing in a South Asian City. Music, Performance and Meaning in Bhaktapur, Nepal. Farnham: Ashgate.