Shamik Chatterjee is an assistant professor at the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) in New Delhi, where he also attained his Master’s in Architecture from SPA’s Urban Design program.

Meaning is evolutionary and contextual. What was once sacred may become everyday over the passage of time. As the community evolves, so does the meaning associated with objects. This change of meaning has occurred most drastically with natural resources and our way of interacting with them. What was once nurtured and used with care becomes industrialized, and, given humanity’s trends, commodified.

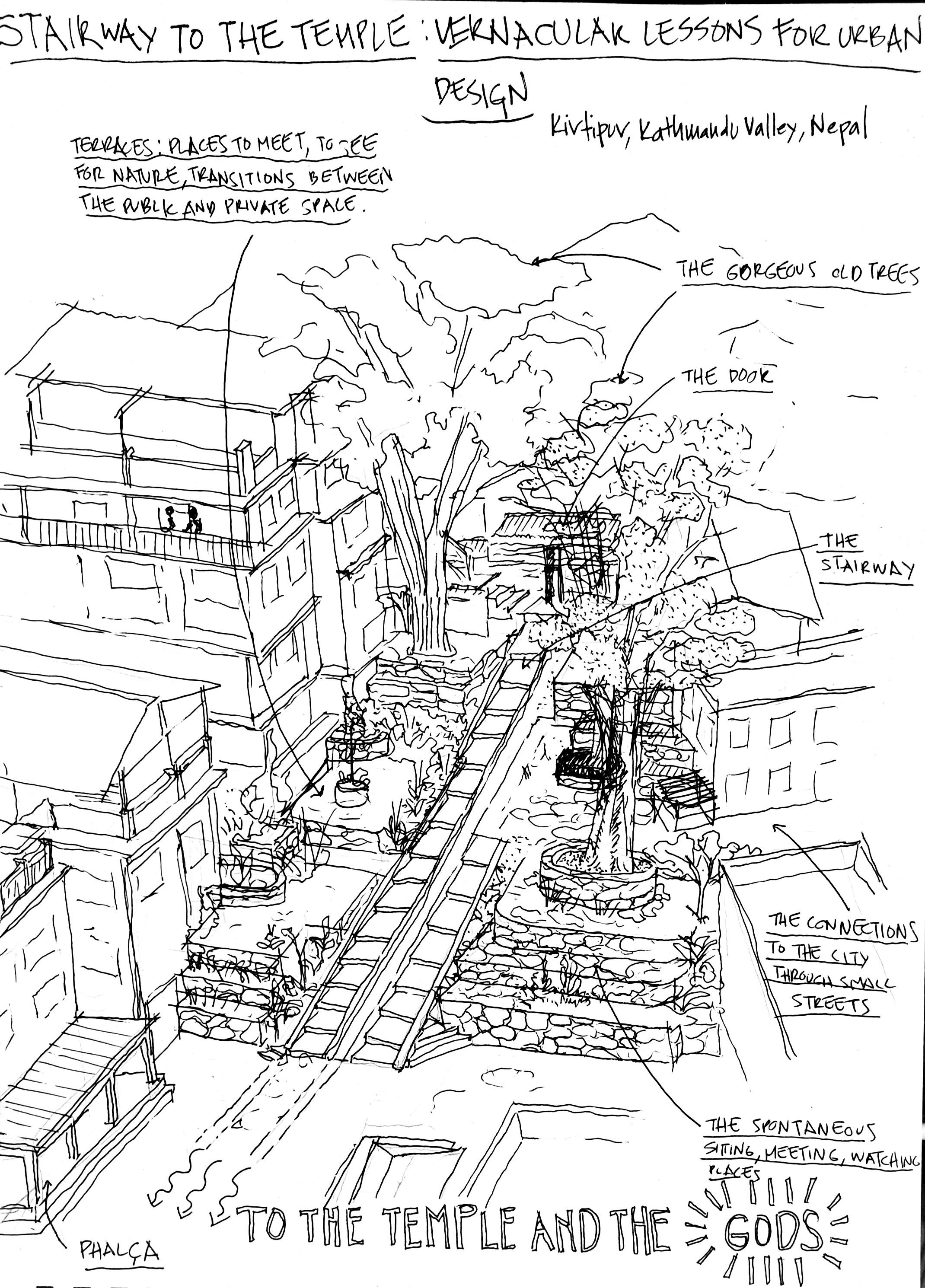

A well in Patan, with a hand pump in the foreground. Plastic jugs and terracotta pots holding potted plants are scattered on top of and to the side of the well. Photo: Shamik Chatterjee

Water is an intrinsic and vital part of our environment. It’s no surprise that, as a giver of life, it becomes revered and viewed as a divine blessing, in all cultures. Our interaction with water can be sacred and ritualistic. But it’s also functional and everyday. We need water for survival, and, hence, had imparted divinity to it in earlier times. This is why we still retain such a strong affinity for water, through spaces and elements like ponds, hitis, lakes, ghats, riverfronts, etc.

A space does not have to be ‘sacred’ to have ‘meaning’. The Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro served a communal function—its space was an everyday space for people across the city. However, even though we have not yet found evidence of any rituals associated with it, we can be sure the structure held significance to the people.

The beauty of such spaces lies in their ability to mold to many uses. The ritual space becomes a space for children to play near the river, a space for women in a conservative society to gather and spend time with each other (without garnering said society’s ire), or even a place to sit and speak soft words to a forbidden lover without being forced to explain oneself. Thus, much like water takes the shape of the container it resides in, many of our most ‘meaning’-ful spaces in a city are those which are accommodating to all and flexible in their use.

Similarly, the old well shown here may not have been ‘sacred’, but I am fairly certain that it held ‘meaning’ to the people who used it. The only evidence I offer is the decorative carving one sees going around the well. It shows a consideration for the well above only utility. Perhaps the families in this neighborhood would use the opportunity of coming to the well to gather water as a time to discuss news or developments in the neighborhood. The presence of a small shrine a little further away showcases the juxtaposition of the sacred and the everyday– a multi-functional space (as an aside, The hitis of Kathmandu are also elaborately carved).

Fast-forward through the ages and we find the hand pump. A manifestation of the effects of industrialization, the hand pump, while being in the same space and giving the same life-giving water, isn’t accorded the same “meaning” that the community once held for the well (or Tun).

Fast-forward some more, and, in the same space, we find our twenty-first-century interactions with water—the 20L plastic storage jugs. Bereft of all meaning beyond cold utility, the jugs showcase our technological prowess and our philosophical devolution. Ironically, they are repurposed to provide a home for another fast-receding natural resource—to serve as containers for plants and small trees, used to beautify the old well.

My fascination with waterscapes lies in the stark divide in how humanity treats water in the twenty-first century versus the sixteenth or seventeenth century, and this picture struck me as being emblematic of that. My gem is this image, showing the evolution of our interaction with a natural resource.