Amanda Taylor is a Ph.D. candidate at SOAS University of London.

Walking around Kathmandu, it is impossible not to see a jumble of cables seemingly precariously balanced atop a pole on almost every street. Some wires hang dangerously low as they crisscross the road. Others, severed, dangle without purpose. And others still are strung in loops, too long for now but perhaps of use in the future.

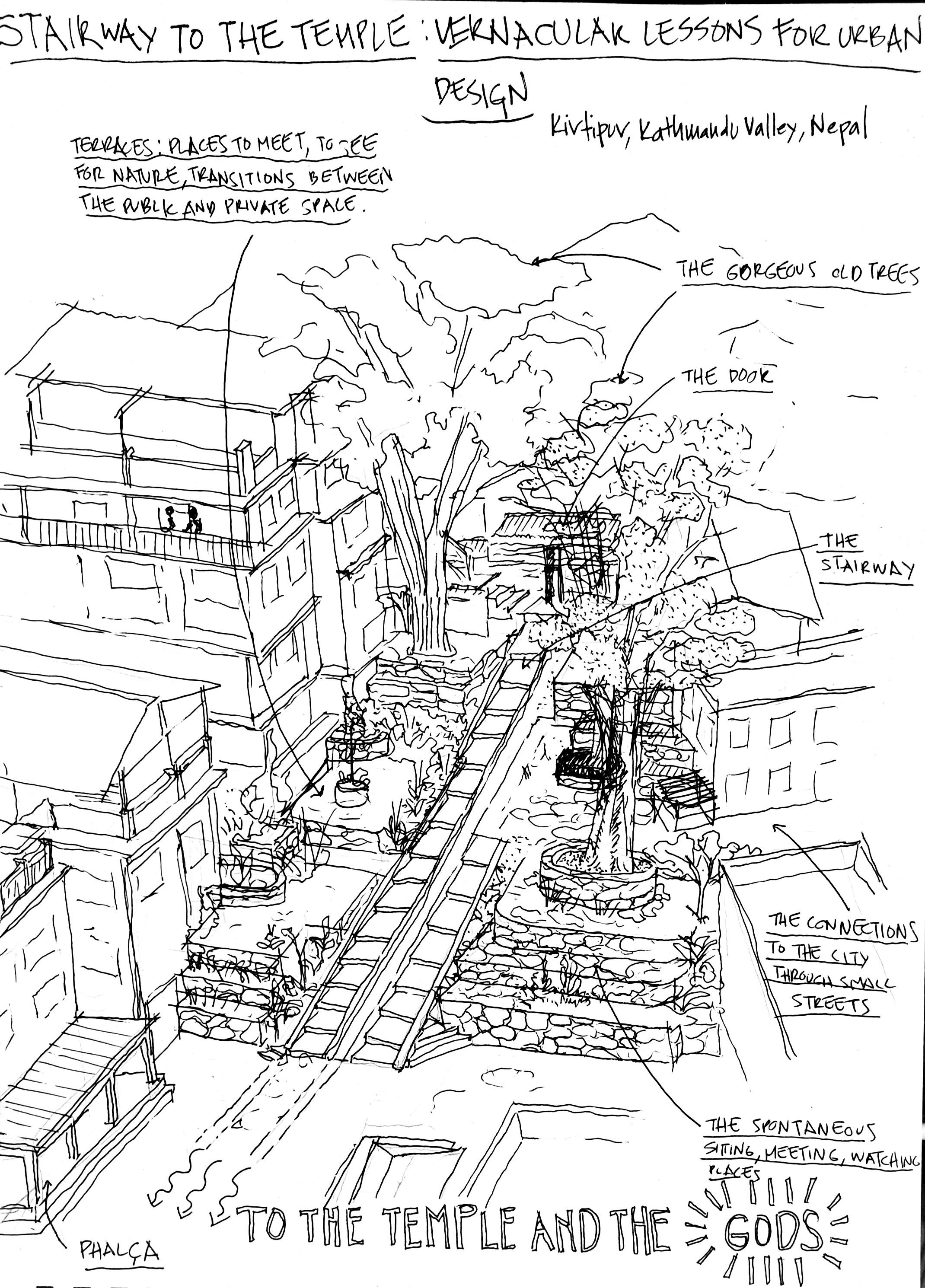

Photo by Amanda Taylor.

These cables are often cropped out of tourist photos. I’ve heard them described as utilitarian and an eyesore, not in keeping with the city’s old shrines, temples, historical monuments, and World Heritage sites. With the advent of fibre broadband, 5G, and other new technologies, it was always likely that these cables would one day begin to disappear, and now the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) has announced that it is planning to remove its poles and move these cables underground (Prashain, 2022). Kathmandu’s streets will soon look very different.

These cables are representative of a particular period of life in the Kathmandu Valley. They very tangibly reflect the rapid population growth and urbanisation that has occurred in recent decades (see Thapa et al. 2008). Often invisible and buried underground elsewhere in the world, here these cables act as a reminder of the physical links between all of us and the places in which we live and work. Connecting private space with public space, they are testament to the relationships between friends, families, local shops and businesses, neighbourhoods, and much more beyond. These electric cables are so recognisable as part of the streetscape that in one art exhibition exploring social-political and environmental issues facing contemporary Nepal, artist Pablo Lopez used them to ‘suggest the entanglement and complicity of solving environmental issues’ (Bikapla Art Center, 2018).

Despite their ubiquity and conspicuity, little has been written about these cables. The prosaic, everyday nature of these cables seems to have resulted in them being overlooked. Vindegg’s (2022) ethnography provides a rare insight into the work of three NEA electricians as they go about their day. Vindegg captures the frustrations of the electricians who are under-resourced and over-worked, as well as those of the wider population, who view the NEA as deeply inefficient. In one example provided, a woman has her electricity meter fitted after waiting two years. Vindegg’s work is a reminder of the wider history that we may be on the brink of losing. Could these cables one day be forgotten entirely? Should they perhaps be considered heritage at risk?

At a cost of approximately Rs15 billion, the NEA hopes that by moving the cables underground, the risk of outages, theft, and electrocution will be reduced (Prashain, 2022). But other changes may of course be brought about as a result. How, for example, will family interactions transform when outages rarely occur? What might happen to those living below the poverty line who can no longer syphon off electricity? Will children be taught about the dangers of electricity when there is not such an overt visible reminder? The impact of the disappearance of these cables could be more profound than anticipated.

For many, Kathmandu’s cables undoubtedly will not constitute heritage. But in the context of their imminent disappearance, a number of urgent questions should be raised. UNESCO recognises industrial heritage and The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage has undertaken a number of studies considering other types of infrastructure as heritage including, for example, the water and oil industries. With this in mind, a debate about what heritage is in this context should perhaps therefore take place. Will these cables be valued more once they are no longer there? Will something that today is considered an eyesore be viewed as a thing of beauty in the future? And, if we don’t want to retain heritage in its existing form, how might we ensure that it is still preserved?

References

Bikalpa Art Center. (2018). Trans Studio Project 3.0. Bikalpa Art Center.

Thapa, R & Murayama, Y & Ale, S. (2008). City profile: Kathmandu. Cities. 25. 45-57.