Diego Jaimes Niño is an architect and an MA candidate in “Cultural Heritage und Kulturgüterschutz” at the Heidelberg Center for Cultural Heritage (HCCH).

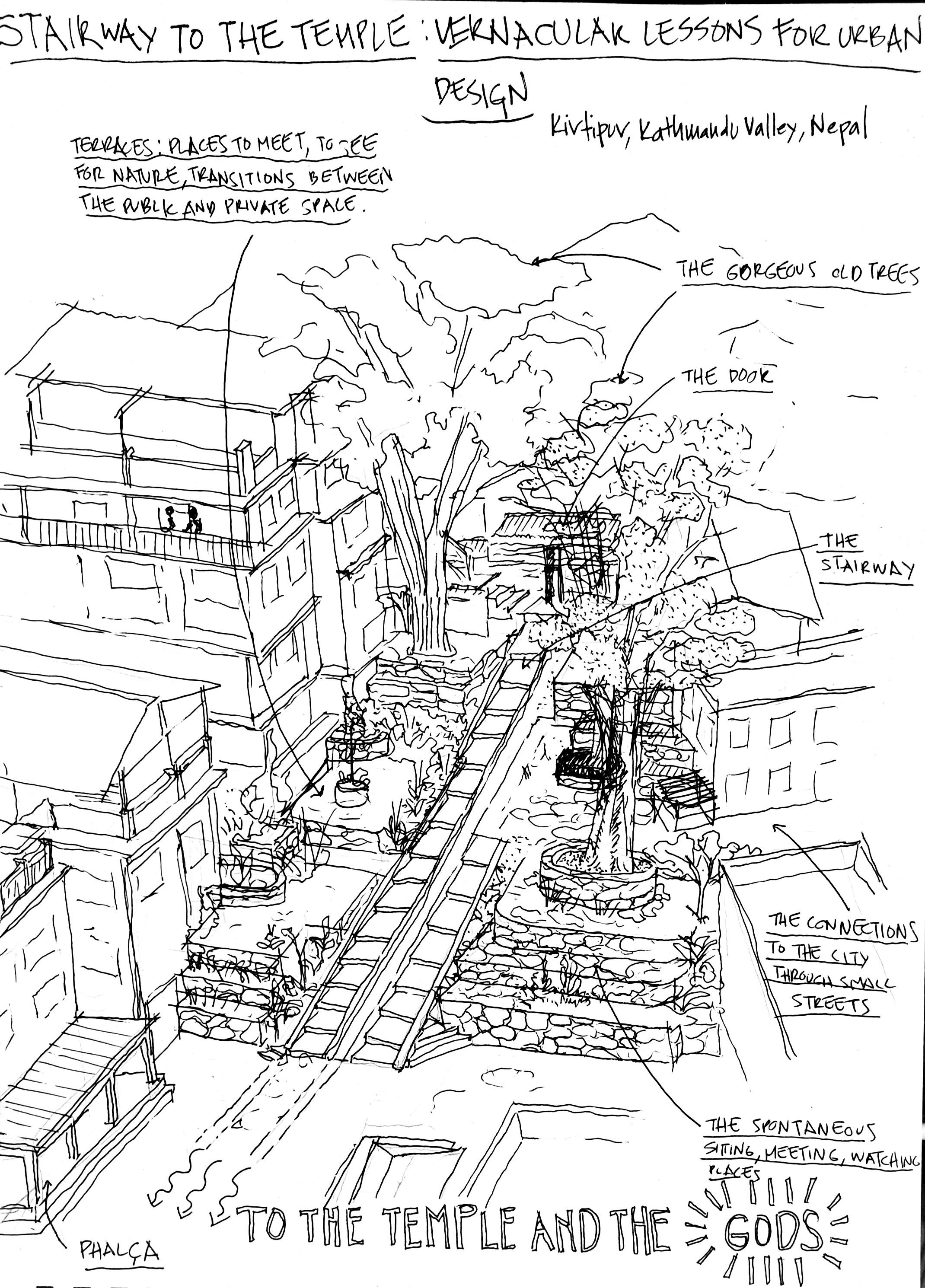

We visited Kirtipur as part of our summer school in September 2022. On the night of the 24th, the group split up to observe ritual processions by musicians (drum players, flute players, dancers), many in Newar attire, fulfilling the ritual lighting of the Ita. From the different neighborhoods of the city, they came together to pay respect to the Indrayani Devi temple. In the final phase of the procession, we crossed an urban door and came to a monumental public space built around a staircase. This is my gem, as I find in it a legacy of vernacular lessons on urban design. It is a built heritage site, charged with knowledge and practices of intangible heritage.

This place goes downhill and connects the Dyo-dwa-kha (Heaven’s Door) with the temple. The door is built in Newari style, wood and brick, with little ornamentation and in a lovely proportion.

Author’s sketch of the Kirtipur staircase and its surroundings. Click to expand.

The central staircase, a “staircase of a ramp” (or rampa caballera in Spanish), comes from a design that was thought to allow the circulation of animals, such as horses or goats. Its design is simple and rational: slanted, long steps and soft counter steps facilitate a slow pace of walking and enjoying the view, or entail the slow, rhythmic pace of a procession. The purity of the staircase’s design stands in contrast with the diversity of urban gestures that happen on its sides: terraces, gardens, other staircases, benches under gorgeous, enormous trees, phalcās, planters, walls, and small squares. Each of the elements flows into the other organically, with smooth joins between them. The assembly appears effortless. It is a kind of space that is difficult to accomplish by design: years, needs, and quite probably the will of the owners of the surrounding houses have given it the quality it affords.

A second outstanding quality of the place is the view: In the foreground there is the central temple, surrounded by various buildings. Further away, there is what can still be seen of the landscape of the valley behind the recent constructions around the temple. The space is a tribune to see the city, and to witness the rituals during the dates of adoration. One may look down to see the temple or sideways to the people coming up and down the stairway. It is a center of the city, and much of its activity is related to intangible cultural heritage.

The staircase and surrounding public space in Kirtipur. Photo credit: Diego Jaimes Niño. Click to expand.

Stairs are among the most important elements of architecture. This place remembered me of the Piazza di Spagna in Rome, and of the monumental stairways of Aztec, Toltec, and Maya pyramids. Although the similarities may not be formal, the relationship they have with the surrounding city and with the sacred are analog.

Although I found no pictures of the staircase that are more than thirty years old, there are old photos of the temple available. They show the place in a rural context: it is known that the temple was built outside of the city’s doors. This puts in evidence that the urban character of the place has developed during the last fifty to sixty years, along with the dense growth of population in the Kathmandu Valley. It is an example of how this city grows, and how “older” heritage gives place to new practices of self-construction.

References:

“Eselstreppe”. RDK Labor Wiki.

Shokoohy, Mehrdad; Shokoohy, Natalie H.: Sagar Shrestha, “Sukra: Street Shrines of Kirtipur,” in

Nepal: As long as the sun and the moon endure. London: Araxus Books, 2014.

Banadur Tapa, Rajesh; Murayama Yuji; Shaliya, Ale: “City Profile: Kathmandu.” In Cities, The

international journal of urban policy and planning. Volume 25 Number 1, February 2008.